Ice climbing in Hyalite Canyon, Montana

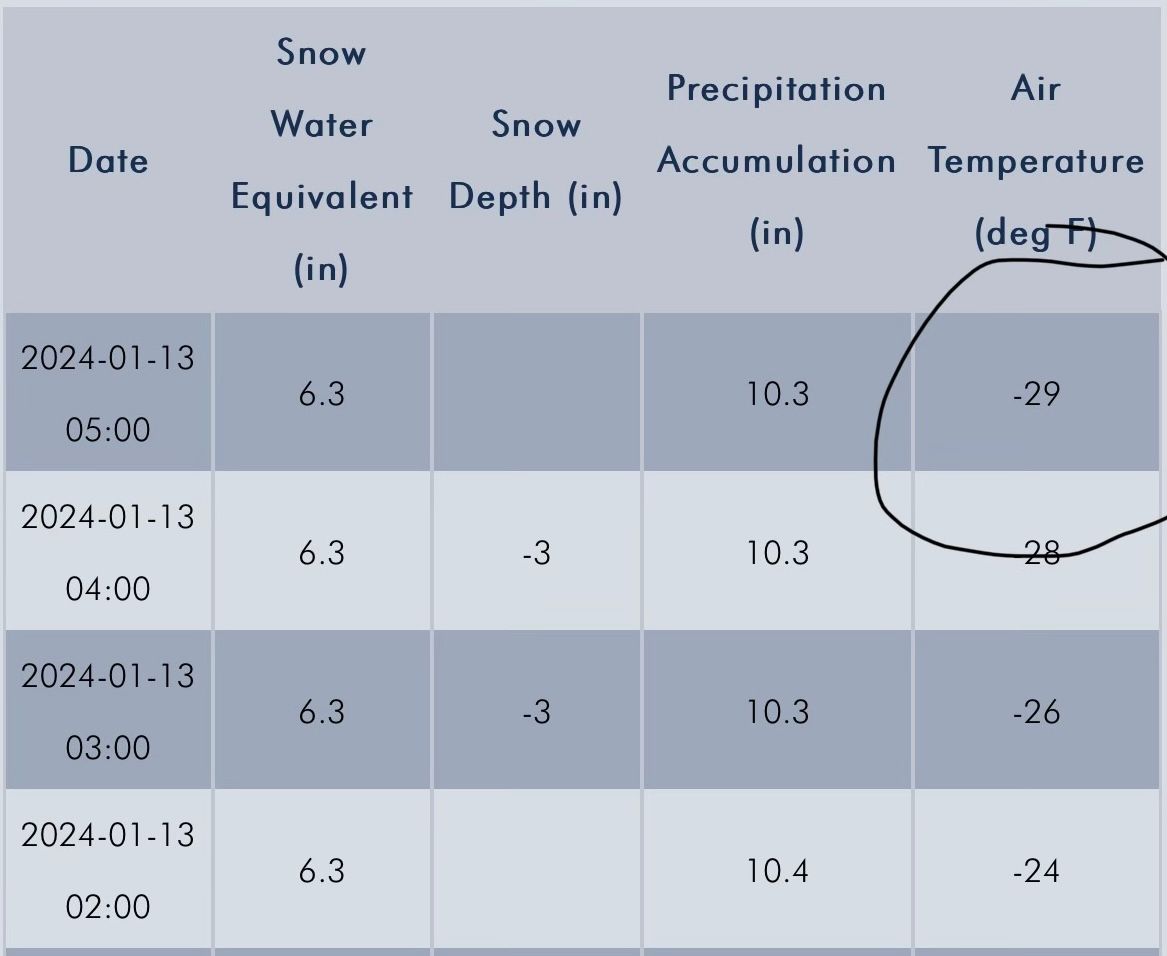

I realized how dangerous the roads were when I had to swerve my truck into a snow berm to avoid rear-ending a semi at a stop sign. We were trying to make a left onto the Montana 287 heading up toward Bozeman and the good traction ended abruptly north of Island Park. The thermometer read -25 Fahrenheit. It was windy too.

Spindrift kicked up into such massive clouds at points during the drive that I periodically slowed to 5 from 50 to let the white-out pass. Rivers and reservoirs along the highway emitted strange towers of fog that caught the headlights of oncoming traffic, setting them ablaze like wildfires.

An airmass fresh out of the Arctic parked itself on top of Bozeman for the weekend I chose to build some ice climbing technique, driving temps perilously low. The ski resorts closed for business. When we got into town, we decided to walk over to Montana Ale Works from the Airbnb to test out the air. It's the kind of chilly that irritates your lungs and worms its way through thick down layers.

I met Henry, my friend and guide for this trip, during a climb up the Easton Glacier on Mt. Baker this past summer in Washington. He grew up in Bozeman and has that classic rugged character that I picture when I think of people in Montana. He's seven years my junior but he carries a professional assuredness that I could only dream of at 24 years old. I liked Henry immediately because he has the same streak of obsessiveness I recognize in myself, where he throws himself into the lore and knowledge surrounding his interests. He talks a lot because he's stoked–also like me. He's a hunter, climber, skier, cyclist and a mountaineer. We're going to be on Denali together in May.

While we were in the Ale Works, Henry texted to suggest pushing back our 7:30am start the next morning by an hour if the temps were still below -20 up in Hyalite. At 5:30am he texted again to confirm we were indeed on for 8:30am.

Opening the front door to bring my climbing stuff out to Henry's truck released a cloud of mist as the moisture from the inside air instantly condensed in the cold atmosphere. The temperature immediately froze all the little hairs in my nostrils, making my nose itch. I started to question this whole deal.

On the car ride over to Hyalite, we caught up about the intervening months since we'd seen each other, and I continued to mine him for beta and stories from Denali.

During his descent from the summit last summer he almost lost the ring finger on his left hand to frostbite as he and a few speedier clients raced down to prep hot water for the rest of the group.

"It swelled up and turned black, and then this sort of sheath of scab fell off in the shower weeks later. There was a bunch of pink baby skin underneath."

He had to be careful on days like this one. Apparently, getting frostbite once makes you more susceptible to it again. Not good for a guy who makes a living off of his hands.

We pulled into the lot. Second car. Henry informed me that this is totally unusual. On a holiday weekend, the lot at Hyalite is packed, even by 8am.

We kept the doors shut to put on our double boots with the heat running, trying to conserve as much precious warmth as we could. Doing this in the passenger's seat is a complicated maneuver involving a lot of squirming. For layers, I was already wearing a fleece, mid-weight puffy, buff, beanie, wool underwear, fleece pants, touring pants, and then a heavy down parka. In reserve, I had my 8000-meter parka (the same kind of thing you'd zip on for Everest) and down belay pants.

We shouldered our packs and headed up the trail to the Genesis area. Fortunately, there was no wind. Henry told me about wind chill charts when we got to the belay area.

"It's pretty much exponential as the air temp gets colder. At this temp [-30F], a 10-mile-an-hour wind almost doubles the chill."

We dropped our gear next to a guide and her two clients from North Carolina (the folks from the other car in the lot). The two guys had made the trip all the way out here, so they felt pressure to give Hyalite a shot. I felt bad for them when I saw they were in single-walled boots. They left within a couple of hours.

Henry led off on the left side of the Genesis 1 feature. It's a big, pocketed ice wall about 80 feet high. Every few moves, he paused to shake out his arms and drive blood into his fingers. It's best to manage how much you sweat by taking your parka and heavy gloves on and off. Henry was in his lighter layers with nothing but fishing gloves on (which offer more dexterity than something like a ski glove, but with far less insulation). Meanwhile, I started to lose feeling in my fingers at the belay with everything on. To fight this, I flapped my arms around like chicken wings to keep my hands on the rope.

After Henry rappelled back down and we switched off belay, I felt perfectly fine in my thick gloves and started my way up the wall. But wearing a beefier glove tends to make you grip harder through all the material and therefore pump out faster. This is what happened to me in the first thirty feet or so. I had to sit back in my harness to take a rest and shake out my arms. On ensuing tries, I learned to love the fishing gloves, which let me ease up my clutch on the ice tools, move faster, and therefore stay warmer overall.

I focused on the technique Henry revised with me at the bottom: Swing, kick, kick. Swing, kick, kick. Level your feet before making the next swing. Use your calves as much as possible to take your weight off of your arms. Place the pick of the axe into natural concavities in the ice to avoid breaking off plates.

When we were finished warming up on the left side of Genesis, I tried my hand at another, more overhung route to the right with the bottom section of the ice detached from the rock. Henry advised I tread more carefully here and just hook into existing divots, if possible, to prevent breaking off huge sections. It was an odd sensation to feel the thrum of the ice when I kicked a foot into it; a deep, hollow percussion. Ice can feel as trustworthy as rock, but there are some moments when you're reminded that you're climbing a gigantic, fragile shard with knives attached to your appendages.

We packed and hiked up and around the Genesis feature to a frozen waterfall above called The Hangover, which you can see clearly from the parking lot. There's a rope strung across the goat path we walked above Genesis to prevent you from tumbling and falling down the routes we just climbed. Years ago at the Bozeman Ice Festival, a woman lost her footing here, fell between eighty and one hundred feet, and landed in deep snow, but, miraculously, walked away fine. "It took a while for the paramedics to believe she wasn't hiding massive internal bleeding. Definitely in that lucky two percent," Henry said.

As we were setting up for the first pitch of The Hangover, I cast an eye over Hyalite. It is strikingly beautiful from that vantage point, and I said so. Henry nodded. "It's one of the most concentrated steep ice areas in the world. Tons of history too. Not far from here, Pat Callis and his buddies pioneered a lot of the early technique. Pat tested out some of the first front points that Yvonne Chouinard designed and sent to him." Before modern ice screws, they'd use piton-like devices called "snargs" and hammer those in to protect their climbs. Before front points, climbers would chop steps to make footholds. It all sounded so laborious.

Though there are many legends, first-ascents, and epics woven into the fabric of this place, you're never quite sure if what you're climbing feels like it did to the initial ascenders. Unlike rock, where you can often climb the same holds as the people who put up the routes, sometimes as far back as the early 1900s, ice is an ephemeral medium. There are people who wait decades for certain routes to "come back in." You can climb a feature one day with a grade of WI 4, and then the next it could be an M6. The flows of ice morph around you, even over the course of an afternoon.

Henry had a story for almost every belay stance. As I took pulls from my half-frozen Nalgene later on our first day, he told me the tale of Forest Fenn's treasure. Fenn was an American poet and writer who passed away in 2020. According to Henry, Fenn felt a deep sense of loss that the West had been tamed. Where would young American men now forge themselves with perilous adventure? In the twilight of his career, he wrote a poem about burying gold treasure somewhere in the western US to inspire a new generation of explorers to get out into the wilderness. A few of these seekers died while trying to find it. But Fenn wouldn't budge on either its location or whether it was actually real. Some thought the treasure to be in Hyalite. Eventually, a medical student named Jack Stuef found the treasure in 2020 somewhere in Wyoming, though Stuef himself refuses to reveal the exact location. The contents were auctioned off for $1.3 million in 2022.

Begin it where warm waters halt

And take it in the canyon down,

Not far, but too far to walk.

Put in below the home of Brown.

From there it’s no place for the meek,

The end is drawing ever nigh;

There’ll be no paddle up your creek,

Just heavy loads and water high.

--Fenn's Treasure Poem

Sounds a bit like ice climbing in Hyalite.

It disappointed Henry that the treasure had been found. "I liked to know it was out there somewhere. There was something nice about the possibility." Who knew? Maybe he'd have stumbled upon it while trudging up to a new route.

After we finished up with the Hangover and its multiple rappels, we descended to Henry's Tacoma. A few cars had pulled in while we were climbing, but we think we had the longest day out.

The next day broke about 15 degrees warmer, about -15F in Bozeman.

"Balmy, isn't it?" Henry declared when I saw him out front.

He drove us up to the lot again and we loaded up packs for the hike to The Dribbles, another climbing area about a 45-minute hike away. This time we booted up outside the car, and the temps (-10F-ish) felt like a normal, very cold day, rather than an expedition to the South Pole.

It's good practice to take a gloved finger and write the name of your destination into the dust on the windows of your vehicle for search and rescue, just in case. It felt a little foreboding, but I scribbled "Dribbles" onto the shell's hatch on the Tacoma, and we set off.

The snow coverage around Bozeman was thin. All of the storm action of the season seemed to have swung southward toward the Tetons and Salt Lake. Getting up from the hiking trail to the foot of the first pitch of the Dribbles required about 500 feet of ascent through dense trees and then a steep portion just below the route. In crampons, we kept raking the loose rock underneath the few inches of snow, which made for very unstable walking. Both Henry and I took falls on our scramble upward.

Looking up at the route was intimidating. Huge steps of ice ziggurat away from you, hundreds of feet high. You can't see the last pitch from the bottom.

My arms were still residually pumped from the previous day and I started struggling just a few moves into the first step. In rock climbing, a 90-degree face is no problem with good holds. On ice, the same angle is harder because it's more difficult to trust your feet and rest on them. You're also swinging sometimes five or more times to get a good stick.

As I felt my arms fatiguing, I paused and changed hands on the tool above me. The other tool I'd hang around my neck by the pick. Hold with one, shake out the other. Switch. Repeat. It's strange how well this works to flush out the lactic acid. After a couple of pitches, I warmed up again and felt like I had my grip back.

It started snowing on us lightly at first, and then more heavily as the day went on.

The ice clearly hadn't been climbed in a while because there were no nice divots we could hook into. I couldn't easily find Henry's placements, so I had to swing on almost every move. I'm not the greatest yet at recognizing good spots to swing--ones that more easily accept a pick and hold it, rather than breaking. I'd often peel off huge plates when I'd strike. One frisbee-sized chunk of ice popped off and cut my arm as it fell past.

This is another huge difference between rock and ice. While rock climbing, it's uncommon that you break off pieces of the wall. And when you do, you yell to make sure your belayer knows there's an incoming missile. In ice climbing, it's just expected that bits fly off as you move. There's no culture of yelling about it. "It'd be like screaming 'Puck!' in hockey," Henry said. The idea is that you place your belayer somewhere out of the way, or at least out of the direct line of fire.

At the belay of the third pitch of The Dribbles, I experienced my first "shelling." It was one of those stances where it's difficult to move completely out of the fall line. As Henry moved up the ice steps, dinner plates of ice began shooting past me on almost every side. I had to keep my eyes up and track the ice in the air to dodge it. Climbers refer to this as shelling because these deadly chunks often sound like artillery, whistling as they rush by. It can be terrifying.

When I crested the top of the fourth pitch, I collapsed on the ground as Henry coiled rope and grabbed gear off of my harness. With all of the adrenaline and focus, I didn't notice that I was starving until that point. "Did you eat anything?" I asked Henry. "Yeah, I've been snacking the whole day." I never noticed. For the whole climb, I'd eaten one or two packs of shot blocks, feeling like I didn't have the time to break out anything more. Now, I tore into my salami and cheese cuts and feasted while taking in the view. The snow picked up a bit heavier, but we could still see the expanse of Hyalite. Powder-dusted pines extending into a foggy haze.

The rappel down was fun, with the final rope length free hanging in a rock amphitheater. We packed up our gear and trudged 40 minutes back to the truck and closed the day with a few beers with Fiona and Henry's girlfriend, Tatum, at Mountains Walking. Henry remarked at dinner that he thought we climbed the most pitches of anyone in Hyalite that Saturday and Sunday just because we stuck out the chill.

As we parted ways, we shook hands. "See ya on Denali," we both said.

So hear me all and listen good,

Your effort will be worth the cold.

If you are brave and in the wood

I give you title to the gold.

--The final stanza of Fenn's Treasure Poem