Who killed the Soviet Union?

For 45 years, generations of Americans and Europeans struggled with and ultimately accepted a nuclear-laden and bellicose Communist bloc, the United Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), which stretched from the Pacific Ocean to the borders of Austria. For a time, it seemed inevitable that this gargantuan amalgam of nations would only expand. Marxist revolutionary governments sprang up in South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia in the decades following the Second World War. Nikita Krushchev, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, declared in 1956 “whether you like it or not, history is on our side. We will bury you!” in reference to capitalist nations.

Now, the presence of such a hostile and massive power, with economic and political systems opposed fundamentally to the West, seems unthinkable. Even Communist China, despite its authoritarian bent and “President for Life,” has, since the days of Deng Xiaoping, embraced a mostly market-driven economy. How did such an enormous coalition, the USSR, materialize and then fade away within the 20th century?

A number of titanic structural problems plagued the Soviet system and portended its destruction. Its command economy and vampiric defense sector siphoned enormous resources away from consumer goods and raw materials production. Andrei Kolesnikov, a senior fellow and the chair of the Russian Domestic Politics and Political Institutions Program at the Carnegie Moscow Center writes:

…In the 1970s, the USSR produced 20 times more tanks than the United States. To a high degree, this was dictated not by military necessity but the need to maintain employment at manufacturing sites. A country that spent its entire existence preparing for war was ruined in an arms race and dragged down by its support for satellite states and “fraternal” communist parties. (Source).

External forces also worked against the USSR. Falling oil prices in the 1980s layered on massive stress, since Russia was almost solely dependent on revenues from oil exports. The scale of its commitments to other Soviet nations, as well as an ill-advised invasion of Afghanistan made it difficult to cut spending. Moscow’s limited access to credit forced the government to print rubles and devalue the currency.

Even with no other intervening factors, it is doubtful that the USSR would have lasted into the 21st century. But it was the well-intentioned thinking of one man in the Politburo that outright killed the Bolshevik project in the early 1990s. He refused to use force to crack down on dissent and hoped to encourage enterprise by haphazardly decentralizing the planned economy.

Mikhail Gorbachev came to power as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1985. During Ronald Reagan’s first term in office, the United States dealt with three consecutive Soviet heads of state: Leonid Brezhnev, Yuri Andropov, and Konstantin Chernenko — each one aged and ephemeral. Reagan would quip at one point that he wanted badly to engage the Soviet leaders in arms negotiations, but “they kept dying on me.” By contrast, Gorbachev was a vigorous 54 years old, the youngest to assume the position of General Secretary since Joseph Stalin. He brought a fresh perspective and sought to depart from the ossified attitudes of his predecessors. In The Cold War, A New History, John Lewis Gaddis explains:

“[Gorbachev] had been aware from his travels outside the Soviet Union before assuming the leadership, that ‘people there…were better off than in our country.’ It seemed that ‘our aged leaders were not especially worried about our undeniably lower living standards, our unsatisfactory way of life, and our falling behind in the field of advanced technologies.’”

Gorbachev, left, with President Ronald Reagan, 1987. Source

Gorbachev’s cognizance of the dire economic situation led him to a policy of “Perestroika,” or “overhaul.” His goal was to align economic growth incentives with a socialist vision. Perhaps, he thought, there was something to the spontaneity and efficient resource allocation inherent in markets. He allowed some state-owned enterprises to choose which products to make and how much to charge for them. By 1988, the Russian people were even allowed some small, privately-owned businesses. Gorbachev attempted to blend Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” principles into a Leninist economic framework, though to disastrous results. But this was not all.

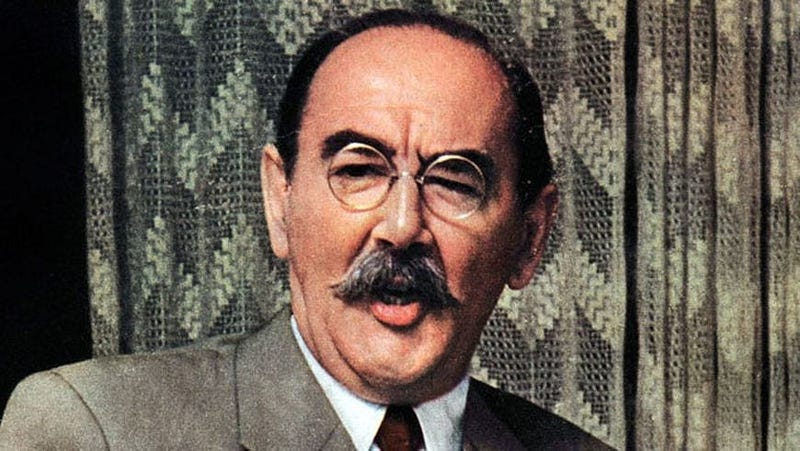

For decades, the relationship between Moscow and the populations of its clients in Eastern Europe had grown more poisonous as the Kremlin repressed dissent and reform. In 1956, Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest and crushed a widely-popular democratic movement. The leader of Hungary’s new, short-lived liberal government, Imre Nagy, was given a short trial and executed.

Imre Nagy. Source.

Prague Spring. Libor Hajsky — CTK/AP Images

1968 brought the Prague Spring, a reformist movement in Czechoslovakia, a member of the USSR, led by Alexander Dubček. His government ended censorship and relaxed restrictions on its people’s freedom of movement. Without limitations on their speech, the Czech people began to openly debate and criticize government policy. This was too much for the leadership in Moscow, who saw such trends as counterrevolutionary. Once the people could speak their minds, who knew what else they’d get up to. Once more, Soviet troops stormed into a sovereign country and ended its liberal experiment, for a time. By the 1980s, Reagan’s caricature of the USSR as an “evil empire” held special sway in a post-Star Wars world.

Gorbachev sensed this acutely. The USSR had a brand problem. This toxic image, he observed, worked against the Soviet people’s quality of life. Western fears of a Moscow hell-bent on a world socialist revolution fed into an arms race that in turn diverted massive sums away from consumer goods and into weapons. Kolesnikov goes on to say:

Rhetoric about the need for NTP — nauchno-tekhnicheskii progress (scientific and technological progress) — came to nothing. In practice, this boiled down to copying Western technologies and producing the most advanced missiles instead of the most advanced shoes and the best guns instead of butter.

If many of these quality-of-life problems could be traced to bad publicity, Gorbachev figured rehabilitating the world’s perception of the USSR would be the solution. “Glasnost” (“openness” or “publicity”), was his policy initiative to transform the world’s perception of the Soviet Union into one of peace, prosperity, and liberty. What this meant in practice was an opening of free speech and elections in member nations and a refusal to use troops to quell protests against the Communist power structure. It also meant massive, unilateral troop reductions, such as in December, 1988, when Gorbachev announced to the United Nations that he would withdraw half a million troops from Eastern Europe.

Both of these policies, Perestroika and Glasnost, emanated from Gorbachev’s earnest hopefulness that the USSR need not use such a heavy hand in its economy or in its foreign policy to hold the Soviet system together. In fact, he thought, the only way to forge a sustainable future for Communism was to give people the freedom to choose. Gaddis quotes Gorbachev from *Perestroika: * “One could always ‘suppress, compel, bribe, break or blast…but only for a certain period. From the point of view of long-term, big-time politics, no one will be able to subordinate others…Let everyone make his own choice, and let us all respect that choice.” His calculation was that the populations of countries like Poland, Hungary, and others, would still choose the Communist party, even if elections were opened to competitors. On the economic front, he thought the injection of profit-seeking enterprise into a system managed by the party bureaucracy would give way to prosperity and individual initiative. In both, he was terribly wrong.

Perestroika was in practice a half-hearted attempt to galvanize growth with free market principles. It left price controls in place, restricted employment opportunities, and left much of the economy in the hands of regional administrators. It also meant less oversight of the cooperatives that ran the state’s many industries. Corruption skyrocketed. Many cooperative managers chose not reinvest profits and instead extract personal wealth. But Kolesnikov says that the key problem with Gorbachev’s reforms was that command over the economy ran against single-party, socialist control. Many of Gorbachev’s colleagues resisted liberalization and he soon found himself on an island between factions of the Politburo who wanted central planning gone altogether and officials who felt their power over various economic sectors threatened. Because state industries were also free to charge more for goods like food, which the people could ill-afford, the economy crunched further. Inflation spiked as the government printed more money to meet the costs of its newly mixed economy.

But the nail in the coffin for the Soviet Union was something less tangible than shortages of grain, or how many bottles of soap Soviet grocery stores stocked. Its biggest problem lay in the high-pressure resentment for authoritarian socialist control building for decades in the populaces of Eastern Europe and the Baltic. Glasnost led not to a more easy-going Communism, but fueled the drive to destroy it altogether.

This drive gathered much strength in 1975, when Brezhnev signed the Helsinki accords, of which the USSR, US, East and West Germany and others were party. Among other things, the accords committed the USSR in principle to “equal rights and self-determination of all peoples” as well as “respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief.” Still, until his death, Brezhnev restrained movements for freedom in places like Poland, where the Solidarity party (*Solidarność) *championed by Lech Wałęsa, an electrician at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk, sought an independent trade union, more rights for workers, lower food prices and more. In 1981, the Polish government, with the threat looming of a Soviet military intervention, declared martial law, outlawed Solidarity, and imprisoned Wałęsa for nearly a year.

Lech Wałęsa. Source.

In 1988, a fresh wave of strikes and unrest swept over Poland. The movement’s chief concern was that the government recognize Solidarity as a party again. By April, 1989, the Polish government capitulated and allowed members of Solidarity to run for the legislature in quasi-free elections, albeit while retaining a quota of socialist party representation. Solidarity took almost all available seats. In the aftermath, all looked anxiously to Gorbachev. The threat of a Soviet invasion eight years earlier cast a long shadow. But in keeping with his embrace of self-determination, Gorbachev chose to do nothing in a remarkable departure from the policies of all of his predecessors.

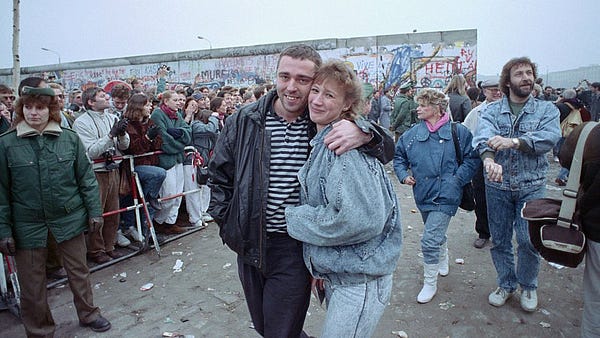

With this, the Polish example served as a rallying cry for other Soviet clients, such as Hungary and East Germany, where Communist party influence crashed in a spectacular deluge of free elections and press. Throughout 1989, the Hungarian government increasingly relaxed restrictions on its people’s freedom of movement. In August, it rolled up the fence that separated it from Austria. East Germans, who could freely travel to other countries in the USSR, began to “vacation” en masse to Hungary, where they, quoting Gaddis, “[drove] their tiny wheezing polluting Trabants through Czechoslovakia and Hungary to the border, abandoning them there, and walking across…By September, there were 130,000 East Germans in Hungary and the government announced that, for ‘humanitarian’ reasons, it would not try to stop their emigration to the West.”

Tears of joy: East Germans crossing into Austria, 1989. Getty Images.

Finally, on the dramatic evening of November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell. The East German border guards, lacking instruction from their superiors in the wake of a strange press conference given by Gunter Schabowski (an official in the East German Socialist Unity Party) where he flatly declared that citizens could travel without prior approval to the West, took it upon themselves to open the gates and let the growing crowds pass unobstructed. Drunken revelry ensued. People from both sides set to work almost immediately with sledge hammers and chisels to dismantle the spray-painted concrete that symbolized decades of painful division. Things progressed quickly from there. Within a year, reunification efforts for the two German states were underway. Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria opened up to free elections. The Romanian Communist leader Nicolai Ceauşescu and his wife were executed by Romanian soldiers on Christmas Day, 1989. Gorbachev, meanwhile, did nothing to impede the regime changes happening within the 15 states in the Soviet Union.

Above: The wall. Source. Below source: Getty Images.

At home, however, he was deeply unpopular. In contrast to his liberalizing foreign image, he was seen as presiding over the complete diminution of Soviet and Russian power. The Russian economy was dysfunctional, quality of life slipped ever lower, and alcoholism ran rampant. His reforms to remove censorship opened the floodgates to domestic criticism. Newspapers and networks lambasted him relentlessly.

On August 19, 1991, a group of Politburo members cut Gorbachev’s lines of communication and arrested him. They installed guards to keep him and his family prisoner in a government residence in Foros, on the Black Sea. Only when Boris Yeltsin, the Russian president, intervened with the support of the police and military, did the coup fail. Gorbachev’s captors released him peacefully. It was Yeltsin who finally dismantled the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and dissolved the USSR entirely shortly thereafter.

Although Yeltsin carried Russia into a new age of democracy and a formal transition to capitalism, it was Gorbachev who, intentionally or not, set these events into motion. For this, he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990.

China stirs a lot of fuss these days: Forcing American and European companies into technology transfers, posturing in the South China Sea; its maltreatment of resident Uighurs. Trump launched a war on the Chinese-American trade imbalance and levied huge tariffs on imports. Despite these headlines, the world’s last remaining Communist superpower is not locked in an ideological death struggle with the US and its allies. The Soviet Union was a different animal. Europeans no longer watch in horror as two sides position intermediate range nuclear missiles on their land. American B-52s no longer make their rounds over the Arctic, waiting for the call to deliver their thermonuclear payloads to Communist cities and military bases. Berlin, once thought to be the flashpoint for a third world war, is no longer sliced up into militarized quadrants. Pieces of its infamous wall litter museums and weight paper on desks around the world.

Much of this credit is due to Gorbachev. His refusal to use force and intimidation to ensure Communist rulers remained in power in Eastern European and the Baltic Soviet states, as had been standard operating procedure for Soviet General Secretaries going back to Stalin, along with his willingness to entertain capitalist economic tendencies prompted the USSR to calve and break apart like a glacier. The Soviet system was ailing when he assumed power, but his policies ushered it more quickly into the dustbin of history. Krushchev’s ominous prediction was exactly wrong.