My Deep Work Experiment

A few weeks ago while traveling, I listened to Cal Newport speak on NPR’s Hidden Brain podcast (episode here). He’s one of many authors in a new series the show launched this summer called “You 2.0”, which is about practical ways to improve your outlook on life, love, work, etc.

Newport’s main thesis is that, if you desire to do great work, you need to focus deeply for extended periods of time without interruption (“Deep Work”). The biggest impediment to your best work, he says, is context-switching, or “pseudo-depth”.

He names numerous thinkers who have employed Deep Work strategies in the past: Mark Twain, Alexander Hamilton and J.K. Rowling — whose retreat at the Balmoral Hotel in Edinburgh was the site where she finished the last Harry Potter book. It stands to reason that most of the world’s most notable artists, scientists, engineers, and inventors hid themselves away from the world, making space for vast stretches of productive quietude.

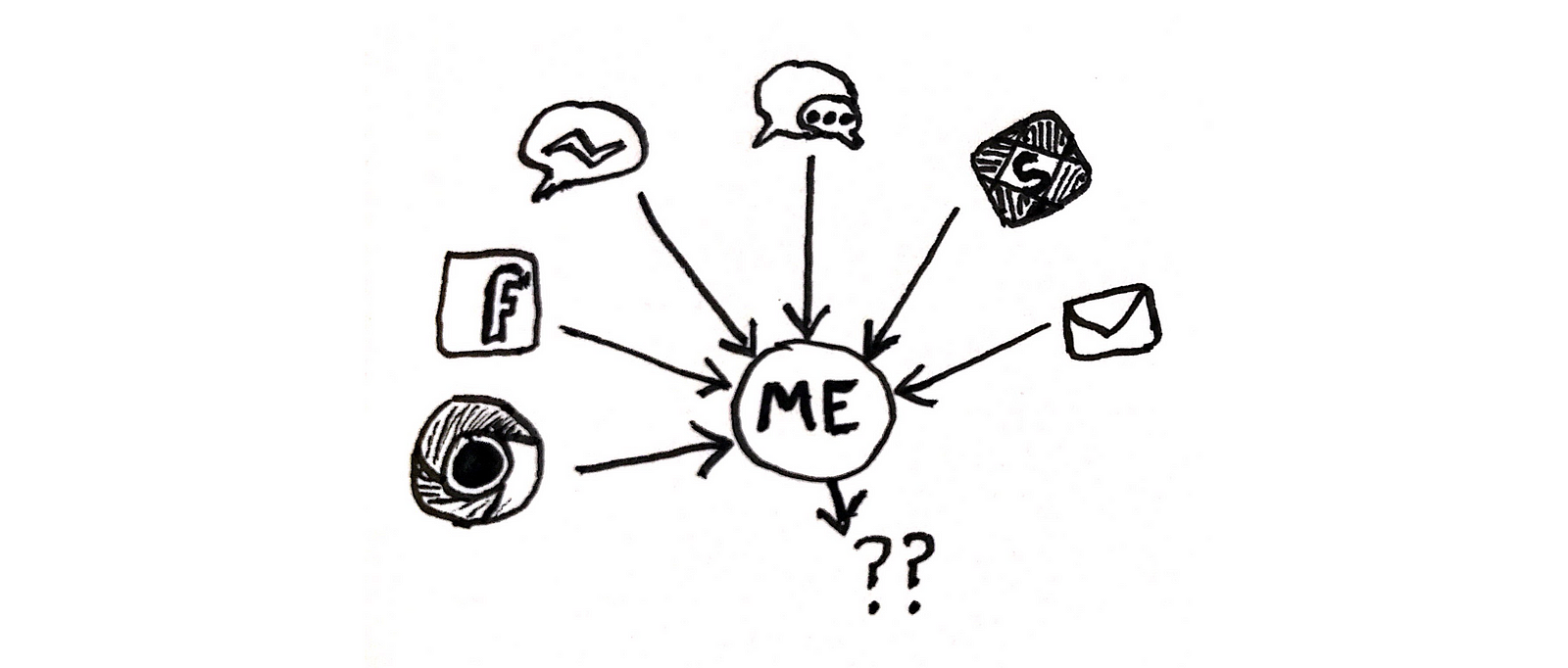

Newport got in my head. I haven’t been able to stop pondering all the small interruptions that cause me to repeatedly switch my mental context while I’m trying to focus. I started to wonder how many books I haven’t read, or how many essays, articles or novels I haven’t written or finished because I’m glued to text messages, or social media, or hopelessly trapped in my inbox.

In a prior article, I wrote about my love for personal optimization through an “agile” form of goal tracking. So, in my current personal sprint, I decided to focus on reducing distraction and finding ways to do deeper work.

However, I should also mention that I regard Newport as somewhat of a radical. To truly follow the Deep Work™ doctrine, one has to make some pretty dramatic life changes. For instance, he praises Aziz Ansari as a shining example to all for quitting the internet. He also proposes that we eliminate email altogether.

These aren’t practical options for me. I’m employed by the internet. I also like the internet, and I think I possess a decent amount of self-control in that realm. The replacements he proposes for email, such as getting rid of personal company email addresses in favor of individual office hours, just aren’t crusades I’m interested in having with my organization. Email, for all its flaws, is entrenched in my company’s culture and it’s not going away any time soon.

As a product manager at eBay, I’m caught in the middle of numerous, parallel work-streams for the product we’re building. I can’t just turn off completely. A big part of the job is being available for designers, engineers, and other individual contributors to clarify requirements, or to work through problems.

However, because another significant component to my job is being creative and crafting a product vision, I need quiet time to think. I want some Newport-style theory in my life, but I need an immediately applicable, incremental version.

Here are some strategies (mostly modified Newport ideas) I’m experimenting with right now:

Killing notifications

Easy…mostly. I find that phone and computer app notifications are constant digital prods that wreck my ability to stay on task. For example, Slack, while disrupting the corporate communication space, also completely disrupts my concentration. I find it irresistible to respond to co-workers while mid-flow on something else if I hear that unmistakable popping sound.

I’ve now muted all apps on my phone and laptop. Chaos was replaced with this odd, quiet bliss. It was a little unnerving at first, but I now feel a strong sense of peace — and I’m only a week into this experiment.

The only thing that I allow ping me now is my computer calendar, which lets me know when I should switch to the next task’s time-box.

I stopped wearing my Apple Watch entirely.

Time-boxing work and communication cycles

Simply declaring that in the following hour, I will do one thing (like write) gives me a strong sense of purpose and keeps me focused.

Likewise, I’m trying to designate three 20-minute compartments (a Newport idea) in my day for communication: A morning, afternoon, and late afternoon cycle for emails, text, and Slack messages.

This is, of course, unless one of my task time-boxes is some form of necessary communication (summarizing and distributing user feedback, for instance).

I don’t always draw time-boxes on my calendar — sometimes I’ll just say to myself “until my next meeting I’ll work on this user story” — but it helps.

Keeping a physical distance between myself and my phone (reducing temptation)

I want my phone around for things like work and family calls, two-factor authentication, etc. but I’ve taken to placing it in my backpack every day.

At home, I’ll just leave my phone in another room.

I’m trying to force myself into a state where I only take it out again when I purposefully mean to catch up on communication during a designated cycle. I think of it like proactive, versus reactive, phone interaction.

Starting on paper, then going digital

I’m jotting ideas down on paper now, away from a screen. Screens are shiny portals to other interesting dimensions, so when I’m brainstorming or trying to work through problems, I now avoid using my laptop.

For story or article ideas, product ideas, or anything else that spontaneously occurs to me, I’ll make note of them first in a Moleskine journal I keep with me all the time.

Those ideas, such as this very article, I translate into digital form when they’re more solidified.

Working from home often, but not all the time

This topic itself is a universe of intense debate, with IBM and Marissa Mayer types on one side (Mayer declares “People are more collaborative, more inventive when people come together”) and the David Heinemeier Hansson and Jason Fried types on the other:

We think she made a big mistake. Because work doesn’t happen at work.

If you ask people where they go when they really need to get work done, very few will respond “the office.” If they do say the office, they’ll include a qualifier such as “super-early in the morning before anyone gets in,” or “I stay late at night after everyone’s left,” or “I sneak in on the weekend.”…

…A busy office is like a food processor — it chops your day into tiny bits. — Jason Fried

Again I find myself caught in the middle here. Offices are giant distraction parties, but face-time is also important. I find that working with people in person — whether in meetings, code review, design sessions — inspires trust and forges emotional bonds that are otherwise very difficult to do over Google Hangouts or Slack.

During the design sprints for our product, I also see that it’s easier to whip up creative excitement about solutions to user problems when we’re all together, in person, drawing on the same whiteboard.

However, in most cases, working from home 1–2 days per week (on days when I don’t have many meetings) reduces the immense time overhead of my commute — 1.5 hours from San Francisco to San Jose each direction — and the repeated taps on the shoulder I get at work which disrupt my focus on any particular task.

Creating intrinsic motivation to complete work

At the end of the day, you have to motivate yourself to do whatever work needs to be done. Distraction is only one side to productivity.

I feel much better when I execute on tedious tasks in a way that doesn’t feel like pulling teeth. Most of the time, I use a mental exercise to fit whatever undesirable task is in front of me into a larger vision that I’m passionate about. If you’re intent enough on the vision, I’ve found that it makes more immediate, chore-like tasks much more palatable.

Conclusion

Last weekend, I wrote a Medium article and read most of a book. I pumped through tasks this week at work, knocking them out one after another.

I’ve found in the past week that simply creating a protected time space, muting anything that could disturb me, hugely increases my happiness and task completion rate (the evidence is in my personal sprint board’s “Done” column).

With these tactics, I’m seizing more of my day and taking back some of my time that previously slipped into the cracks. This experiment is probably here to stay.