A review of our year on the road

I'm slowly caffeinating and jotting notes for this piece while taking in the morning glow. As the sun crests the Mule Mountains, the golden light spreads itself over the gulch that clutches old-town Bisbee, Arizona. My wife's family lives here and we're visiting again for the holidays. I wrote about this place earlier this year, before all the craziness of 2022. It's a strange and storied old copper mining settlement near the border of Mexico, just north of Naco. The scene out of the window in front of me is peaceful, and it reinforces that I haven't had enough of these kinds of moments lately. This year of nomadism was terrifying, beautiful, and probably the most intense period of introspection in my life thus far.

Motivations

I've wanted a taste of the itinerant life for at least a decade. The hedonistic appeal is obvious: Do cool stuff in places you haven't been, eat and drink delicious new things, and meet interesting people. The philosophical appeal is straightforward too: The open road might help you find meaning in your life. On top of having such short existences, our exposure to ideas, projects, or passions is constrained by our initial conditions, like our parents' values, socioeconomics, time, and place. Cranking the valve open on the experience firehose, I thought, might break me out of some of those constraints; might help me get a better idea of which projects I want to dedicate my life to.

The other piece of our decision to nomad around was to sample cities. I've only lived in two places for an extended period as an adult (Salt Lake and San Francisco), and Fiona hadn't lived in many more than that. If you're counting towns that we moved to of our own volition, rather than being located there by our parents, it was even fewer: A total of one for me. We had it in the back of our minds that we'd settle down in a place for the rest of–or a big chunk of–our lives. Chances were, we figured, some town in the US would speak to our souls. So, this nomadic endeavor was more like research, we figured.

I still think there's some truth in this, but, at the end of the day, we just wanted to have fun. And with remote work becoming so commonplace in the era of COVID, it was pretty easy to set in motion.

Figuring out a nomadic method

Once we committed to the idea of life on the road, we had to decide on the way we wanted to do it. There are nearly endless permutations, but they all come down to pretty much four factors: Discomfort tolerance, money, trip length, and career goals.

- Discomfort tolerance: How many modern luxuries can you sustainably part with? E.g. a full kitchen, a proper bed, a proper bathroom, etc.

- Trip length: Is this a one-month thing? A multi-year thing?

- Money: How much do you want to spend on your nomadic equipment/accommodations? e.g. van, car, Earthroamer, Airbnb.

- Career goals: Are you trying to keep up a professional career on the road? Are you going for a climbing or ski bum lifestyle?

Once you answer these questions, the method you select becomes more obvious. A high discomfort tolerance, a trip length of a few months, an unwillingness to spend lots of money, and a goal to climb, ski, or hike without working could all point to car camping as a good option.

For us, the decision was a pretty easy call. We essentially wanted our normal lives but in different cities. Maintaining our professional work was paramount and, based on our planned year of nomadism, we knew we wanted a situation (and the comforts) to make that easy. So, we rented Airbnbs for about a month at a time in different places and commuted between them in our car. We also found this way of traveling to be pretty nice because, once we moved into a new city, we didn't have to tote all of our valuables everywhere we went, as you would have to if you were in a Sprinter van. But the tradeoff is that picking up and moving to a different city is more cumbersome.

We did, however, decide to modify our car setup a bit because we wanted to do some offroading and a lot of camping along the way. The video below walks through our gear:

Learnings

Hire guides and imbibe some intensity.

I found that simply being in a new place isn’t enough of an experience generator by itself if you’re aiming for a perspective shift. Getting out and doing stuff, preferably with locals, is key. Attempting challenging things with them is even better, like ice climbing, mountaineering, or fly fishing. Since it wasn’t the case that we had friends or family in many places that we went, I’d go with guides. In a few cases, I became friends with them outside of the activity. Bryson, my fly fishing guide, turned into my drift boat buddy and I’d help him load the boat on the trailer and drive between the start and end points of our fishing float in exchange for free guidance on the river.

Local people also tell you stories about the area you’re visiting and I found that once I understood the mythos of a place, I appreciated it more. The Grand Teton, for example, would for me just have been a very large piece of rock if I hadn’t come to learn about the harrowing tales and reverence the guides had for that peak. All the people killed by lightning up there, the beauty of the sunrises on the surrounding summits, and the victories of local climbers establishing new ascent lines. As we climbed, they painted a picture of its majesty and its terrors. These things blended with my own experience on the climb and I came away with a semi-religious fervor for mountaineering. Now, I’m targeting a Denali climb in 2024.

A deeper look at my Grand Teton experience:

Constant movement creates enormous amounts of stress. Pacing makes everything more sustainable.

Fiona and I are both pretty tired. This year's constant movement created an undercurrent of chaos and stress that, even now, makes us feel uneasy when we should be enjoying time with family and friends. We thought that this would be an anomalous year and 2023 would see us return to the Bay Area and our offices there. That pressure made us want to make the most of it and created in us a kind of “GO GO GO” attitude all the time. But moving so often, we worried constantly about getting work done, exercising enough, and having enough time for personal creative projects. On top of it all, we were concerned about the security of our stuff in those moments of transition. Often, our car, with all its valuables, would be parked on a busy sidewalk as we ferried our gear into places like our pad in New Orleans.

Doing it all over again, I would target at least two months in each location. In places like Austin, Texas, I felt like we were only just getting into a rhythm when our month was up. For us, working on the road, we had to learn that we shouldn’t plan it like a vacation with a tourist schedule, where you might spend a week here and a week there. The months where we had weekly transitions were the ones I was least excited about.

Stay near the party, not in it.

Staying in the French Quarter of New Orleans sounded great on paper, but the reality of being there for a month while trying to maintain jobs and normal routines turned out to be less than ideal. I wrote in a newsletter installment in October: “we thought [it] would be a dreamlike place to crash…Except, we didn't account for how tiresome the debauchery would get in this part of town. It's not uncommon to see some heavyset man clutching one of those neon-green jugs of hurricane cocktail puking his guts out on the street. Saturday morning smelled like urine as I went out for my run. Tourist trash heaps up in small piles in the gutters. Parking anywhere close to our apartment is a nightmare. But hey, the French architecture is cool.”

From now on, we’re going for more “quiet suburb” than anything else.

Alone time is sacred. Bake it in.

We had housemates for the whole back half of this year. Our friends and family are great! But the constancy of it for six months straight, after living alone for five years, was hard. Having other people around makes it more difficult to establish many of the mundane routines, like eating, exercise, and work, which are already challenging on the road, because you just have to factor in the schedule and preferences of the other people you’re staying with. Setting boundaries around who can stay with you and for how long gives you sanity. Next year, we’re planning on zero extended stays with housemates.

Conclusion: Nomadism accelerates self-discovery.

Stationary life makes creating community and routine a lot easier, and those things are important. But, if your goal is to push outside of your comfort zone, sink into novel places and explore new concepts of meaning, it's all but impossible to do with the standard American vacation schedule (two to three weeks per year somewhere other than home and work). Regularly living in new places gives you nights and weekends to absorb them and a chance to feel like a local.

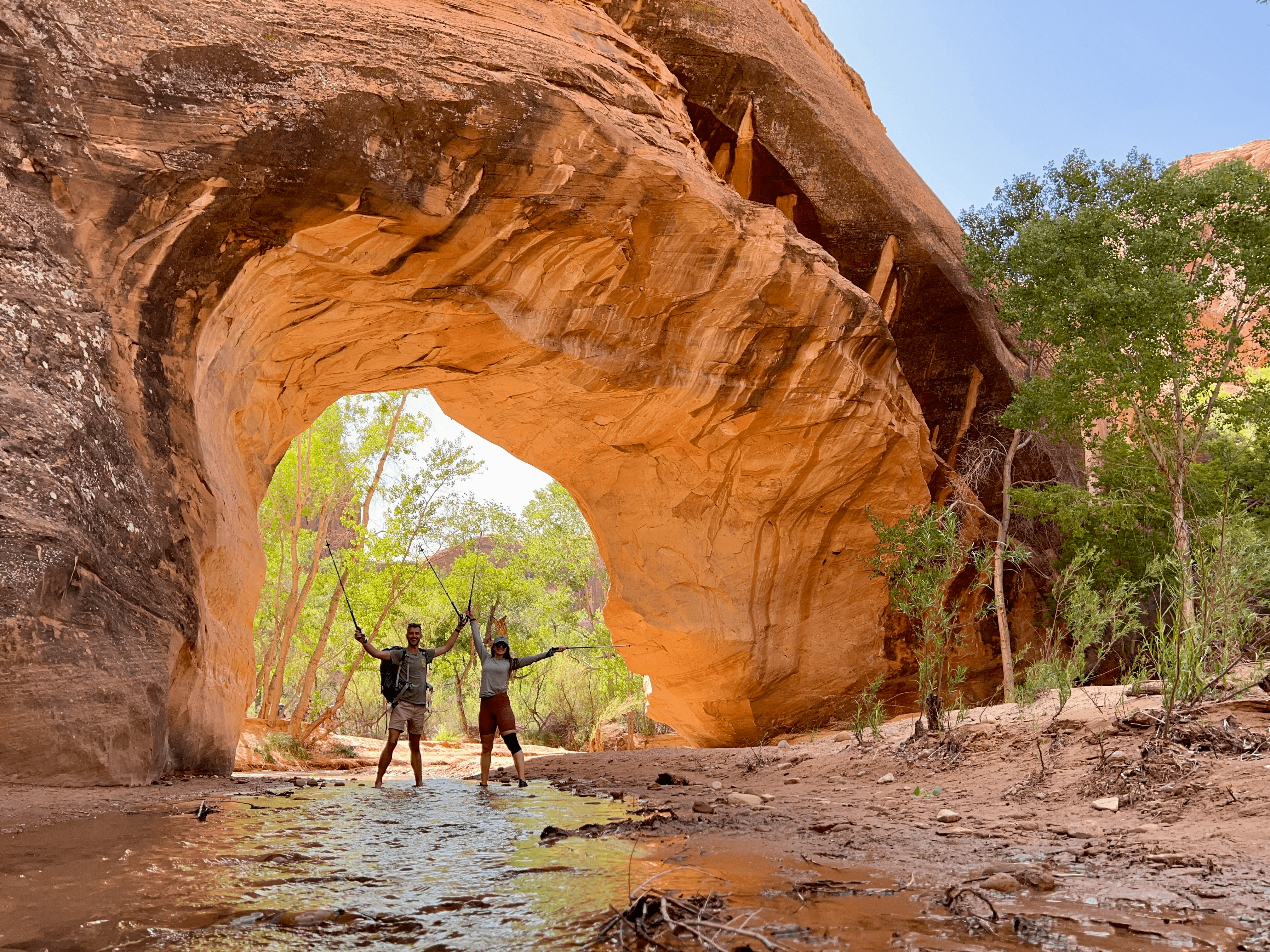

And, the city sampling worked for us. After spending a lot of time in southern Utah and Driggs, we realized that we’ve been desperately missing mountain life. We ended up buying a house in Victor, Idaho, to give ourselves permanent access to the wilderness, for at least part of the year. The idea is to rent the place out when we’re not there and keep traveling–though with a few modifications to our pace. I now think the ideal kind of lifestyle for our goals (sanity, professional career growth, and a hint of danger) is six to eight months per year in our Idaho base camp with one or two other long stays for the remainder.

It’s probably obvious from the existence of this newsletter as well, but I learned to enjoy this flywheel of adventuring, making stories, and documenting them with words or a camera, which leads to more adventures and more words. So, stay tuned for more!