Broken Arrows and Almost-Annihilations

Available on: Spotify, or Apple

We still live beneath the sword of Damacles, though we tend to forget it. The generation of humanity who knew a world without nuclear weapons before 1945 is fast disappearing and the last time humanity seriously stared down armageddon seems long ago.

Dan Carlin thinks that our forgetfulness is natural. Perhaps, he wonders, this is a kind of evolutionary advantage. It’s debilitating to maintain a state of peak fear. It takes you out of the present. Prevents you from enjoying your stay on Earth. To many of us, nuclear weapons are too abstract, too distant to remain top-of-mind.

But now and again, we’re reminded of what’s at stake. Fred Kaplan points out in his introduction to The Bomb: Presidents, Generals and the Secret History of Nuclear War that current events, such as the recent tensions with a nuclear North Korea, thrust us into remembering what unchecked, maniacally destructive power rests solely in the hands of the US president. As of March 1, 2019, the United States has a combined 656 deployed Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs), Submarine Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs), and heavy bombers. This amounts to 1365 individual nuclear warheads of variable power, inclusive of the B83 thermonuclear bomb, with a blast yield 80 times more powerful than the weapon detonated over Hiroshima, Japan, during World War II. The Russian Federation, the United States’ counterpart in the New START (Strategic Arms Reduction) treaty, possesses similar numbers of deployed launch platforms and warheads.

When we wake up to these facts again, it is helpful to remember that these numbers are merely a fraction of what they once were. And though the current US relationship with Russia and certain other nuclear players remains icy, we haven’t come close to the crises of the Cold War in recent years, where the survival of humanity was in question minute-to-minute, and the probability of accidental detonations surged. Below are several, particularly unnerving examples of each, sampled from much larger lists.

A quiver of Broken Arrows

Unexploded nuclear bombs still lay unfound off American coasts, embedded in swamps, 16,000 feet below the Pacific Ocean’s surface, and elsewhere. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, as the Cold War went into full swing, increasing tensions caused both sides to ratchet up military activity in an effort to stay ready for making or countering a nuclear attack. With so many planes, ships, missiles, and submarines deploying, accidents began to happen. A lot of them. Submarines malfunctioned and sank. Planes crashed, or fell off carriers. In the process, nuclear ordnance began to go missing or very nearly detonate by accident. The US military refers to these as events as Broken Arrows. Specifically, the “accidental or unauthorized detonation” or “seizure, theft, or loss of a nuclear weapon or component (including jettisoning).”

Chrome Dome

When the Soviet Union launched “Sputnik,” the world’s first satellite, into orbit, the US Air Force panicked. According to Matt McCormick in *Buzz One Four, *leaders like General Curtis LeMay of Strategic Air Command (SAC) reasoned that if the Soviets could launch satellites into space, they could also lob nuclear warheads at the US mainland without the use of manned aircraft.

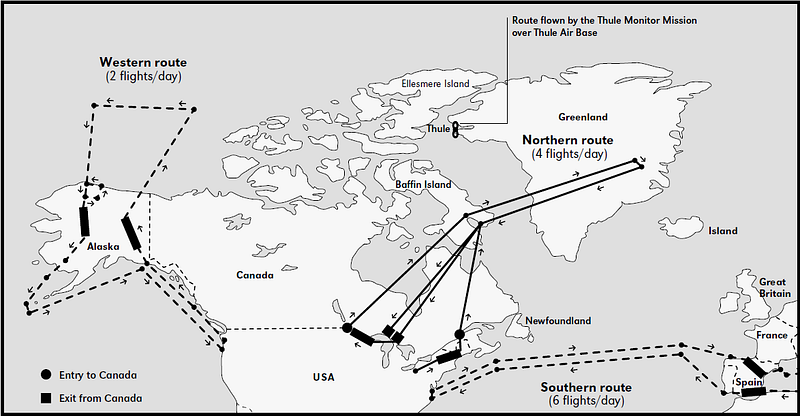

The Air Force launched “Operation Chrome Dome.” This put twelve B-52 thermonuclear-laden bombers on pre-planned attack vectors aimed at the Soviet Union 24 hours a day, seven days a week from 1960 to 1968. The mission was to enforce deterrence by looping near Soviet airspace over the Arctic and the Mediterranean. If the Soviets were to destroy US missile, bomber, and submarine bases with a missile attack, SAC wanted enough bombers airborne to threaten enormous damage in retaliation.

Insignia and patch of the US Strategic Air Command, meant to symbolize peace-keeping with the threat of godlike force.

Such a massive and ongoing procedure led to problems almost immediately. During the years Chrome Dome ran, five B-52s crashed with thermonuclear weapons on board:

- 1961: Goldsboro, North Carolina. A B-52G broke up in mid-air, jettisoning its two thermonuclear bombs and killing three out of eight crew members in the process. One of the Mark 39 3.8 megaton bombs completed *all but one *arming step required for detonation.

- 1961: Yuba City, California. Four crew members ejected. Four thermonuclear bombs were recovered from the crash site.

- 1964: Savage Mountain, Maryland. The basis for Buzz One Four. Three out of five crew members died when the tail of their B-52 broke off in high turbulence over Maryland (a known issue with early models of the bomber). Its two thermonuclear bombs, each with a 9-megaton yield, were found in the center of the fuselage wreckage.

- 1966: Palomares, Spain. A B-52 collided with a KC-135 at 31,000 feet during a mid-air refueling operation. All crew members on the KC-135 perished. Three of seven B-52 crew members died. Four bombs scattered near Palomares, two of the bombs’ conventional explosives detonated, contaminating a large area with plutonium debris.

- 1968: Thule Air Base, Greenland. A cabin fire caused the crew of the B-52G to eject, resulting in one fatality. The plane crashed with four Mark 28 bombs on board. The conventional munitions exploded causing radioactive contamination as pieces of the nuclear bombs were strewn around the crash area and a joint clean-up effort with Denmark ensued.

Chrome Dome flight routes. Source.

Titanic troubles

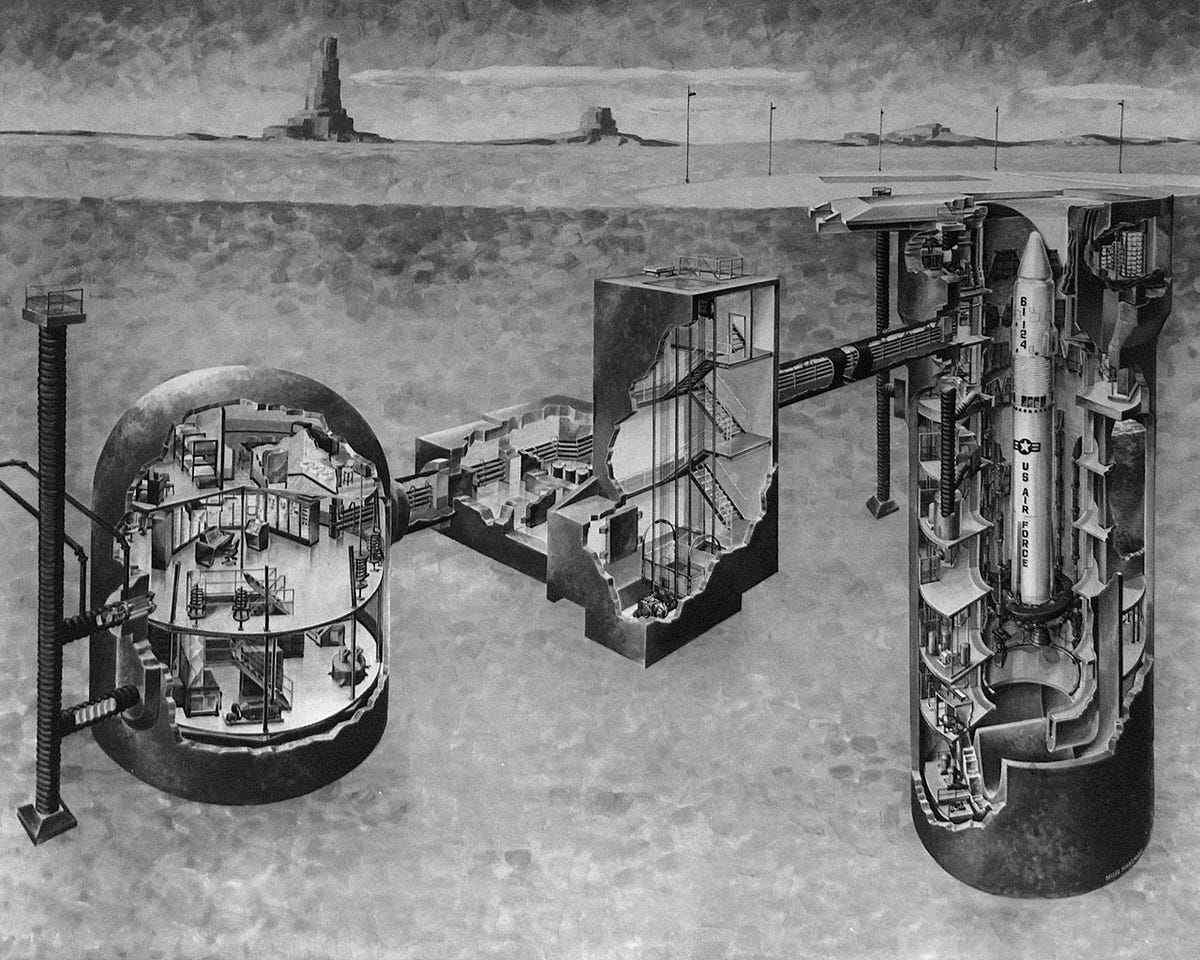

By 1980, the Titan II missiles, then 18 years old, showed their age. Airmen at the time complained frequently about fuel leaks and faulty vapor detectors in the silos. These were the first missiles that the Air Force could fire from an underground silo, unlike their above-ground launched predecessors, and which, when capped with a 740-ton blast door, made them very useful as a counter-strike weapon. The missiles carried the largest-yield warhead ever mounted on an ICBM by the United States: The 9-megaton W-53.

On September 18, 1980, at missile complex 374–7, Damascus, Arkansas, Senior Airman David Powell, a 21-year old missile repairman from the 308th Strategic Air Wing’s Propellant Transfer System (PTS) team, began a routine maintenance procedure to restore pressure to the second stage oxidizer tank. The Titan’s engines relied on a hypergolic reaction between Aerozine-50 and the oxidizer, nitrogen tetroxide, to create an immense amount of thrust.

As Powell unscrewed the pressure cap in order to add ordinary nitrogen gas to increase pressure on the oxidizer, he dropped the nine-pound socket attached to the wrench. It fell through the small gap between the maintenance platform and the missile’s skin 70 feet down the silo, ricocheted, and punctured the first stage fuel tank, causing a jet of Aerozine to spew into the silo.

The launch duct at the Titan II Missile Museum, AZ. Source.

After many attempts to diagnose and fix the situation, the missile crew and PTS teams evacuated the complex. They were worried the decreasing pressure of the fuel tank would cause the entire structure of the first stage to collapse with the weight of the second stage and the warhead sitting on top. If this happened, it was almost certain that the oxidizer and fuel would mix, setting off a massive, uncontrolled explosion. And the warhead…no one knew for certain what it would do.

Another airman, David Livingston, attempted to re-enter the silo in order to switch on an exhaust fan to vent the fuel vapors. However, during this process the fuel flooding the complex ignited, causing a massive explosion that sent the blast doors flying and ejected the W-53 cone about 100 feet away from the silo. Huge pieces of concrete and rebar rained down on the crowd gathered outside. Livingston died of his injuries.

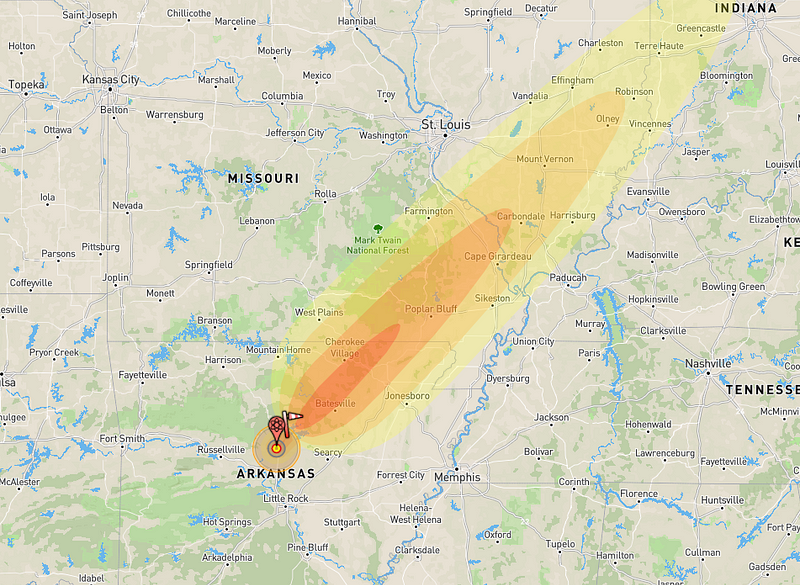

Fortunately, the warhead’s safety features held. A 9-megaton ground blast would have emitted a cloud of fallout spilling into four different states, causing thousands of fatalities and injuries.

NUKEMAP simulation of a 9 Megaton surface detonation in Damascus, Arkansas.

All told, the US Defense Department recognizes 32 Broken Arrow events between 1950 and 1980.

When it’s almost come to blows

During the Cold War, the continuation of the human species periodically came down to a guess or a bluff by a single person.

Oft-quoted Secretary of State Dean Rusk, in reference to the posturing between the US and the Soviet Union that nearly brought the two countries to all-out nuclear war in the 1960s, called the state of affairs a “goddamn poker game.” It’s an apt comparison.

Berlin and the backyard

But if nuclear deterrence was a game, Nikita Krushchev didn’t think much of his new opponent after the 1960 US election. The Soviet leader formerly squared off with Dwight D. Eisenhower, the five-star general and Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe during World War II — himself apparently a master poker player. Comparatively, he thought of John F. Kennedy as something of a spoiled softie: A baby-faced aristocrat, well-known for womanizing and hanging about with the likes of the Rat Pack. Not used to a hard life. Krushchev was 23 years Kennedy’s senior. Though born a peasant, he ascended in the Communist party, participated in Josef Stalin’s purges and took part in the bloodbath defense of Stalingrad against the Germans in World War II, during Hitler’s ill-fated Operation Barbarossa.

Kaplan details the June, 1961 summit between the two men:

“It proved disastrous. Kennedy had hoped to calm tensions and avoid a crisis. Khrushchev…berated him repeatedly, vowed to sever Berlin’s Western ties by the end of the year, and warned that the Soviet army would go to war if the West tried to maintain its access. Boarding the plane back to Washington, Kennedy mumbled to an aide, “It will be a cold winter.”

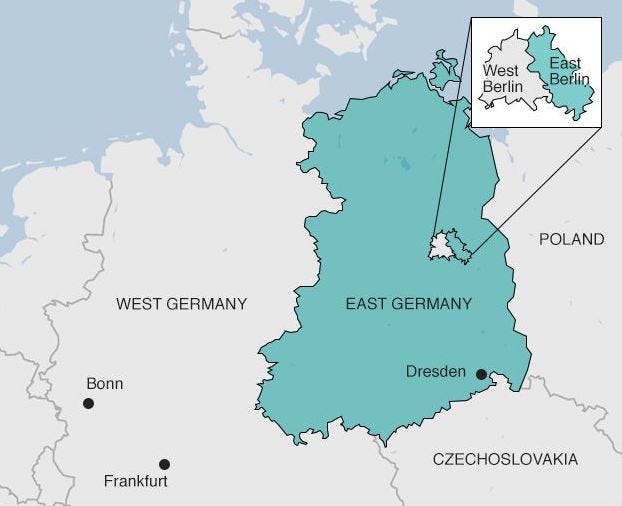

Allied-held West Berlin became a thorn in the side of the USSR quickly after its inception in 1949. It sat 100 miles within Communist East Germany and became a staging ground for East German citizens attempting to flee to the West. By 1961, 4.5 million East Germans had emigrated to West Germany or West Berlin. These were primarily highly-skilled professionals: engineers, doctors, and lawyers, representing some 20% of the East German population. To stem this outward flow, Krushchev wanted to push the US and its allies out of the city and return control to the East Germans. The East Germans constructed the Berlin Wall and the USSR repeatedly signaled that it would forcibly take the rest of the city.

Krushchev also relied on the ominous threat of the “Missile Gap,” which was the idea that the Soviets were far ahead in both their numbers and efficacy of ICBMs than the United States. With this rhetorical tool, his calculation was that the United States would not retaliate against a conventional ground invasion of West Berlin for fear of a strike on the US mainland. Throughout late 1961, East German police began to interfere with or deny access to US diplomats crossing into East Berlin.

Depiction of West Berlin relative to the rest of Germany. Source

But Kennedy wasn’t having it. With the help of the Discoverer satellite’s photography, U-2 reconnaissance spy planes and human intelligence, Air Force analysts debunked Krushchev’s missile threats as baldly overstated. The number of long-range missiles possessed by the Soviet Union in 1960 looked to be merely four.

Kennedy authorized a speech by the Assistant Secretary of Defense Roswell Gilpatric to announce the numbers and capabilities of nuclear weapons available on both sides and emphasize that the United States had a clear and overwhelming second-strike capability if the Soviets were to make a first move: “their Iron Curtain is not so impenetrable as to force us to accept at face value the Kremlin’s boasts.” The US wasn’t just going to walk away from Berlin.

Events came to a head on October 28, when General Lucius Clay deployed M48 Patton tanks to Checkpoint Charlie along the border between East and West Berlin in an effort to enforce US freedom of diplomatic movement. The Soviets responded by moving an equal number of T-55 tanks to the opposite side of the checkpoint. Each force trained its guns on the other and the staring contest lasted 16 hours until backchannel communications defused the situation.

With his long-range missile program publicly discredited for the meantime, Krushchev began looking elsewhere for a lever to dislodge the US from Berlin. He found one in Cuba.

Fidel Castro recently cemented his control of Cuba after the failed Bay of Pigs disaster, an attack by CIA-trained Cuban guerrillas to attempt to retake the nation and install a non-Communist, US-friendly government. Castro crushed the counter-revolutionaries in three days. A woefully embarrassed Kennedy took the lesson to heart.

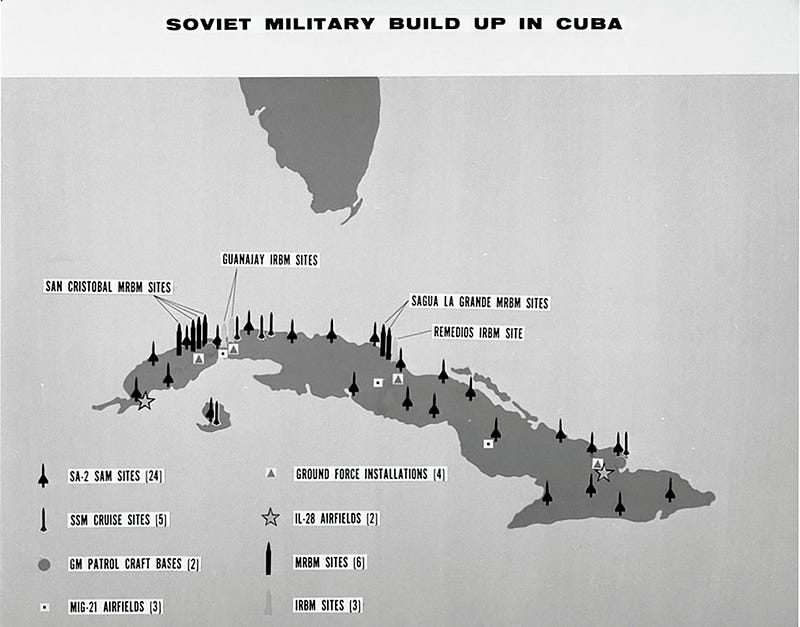

In a chance flyover by a U-2 spyplane in October of 1962, the US discovered medium-range Soviet ballistic missiles on the island. Kennedy’s ExComm (Executive Commitee of the National Security Council) went into overdrive. Over the next thirteen days they debated how to proceed, getting little sleep. Most of the Joint Chiefs of Staff wanted an immediate and forceful airstrike to take out the missile sites. Kennedy demurred. He worried that dead Russians in Cuba would mean a clear escalation, giving Krushchev the excuse to seize Berlin, throw the confidence of NATO off-balance, and create a rapid spiral into general nuclear war.

Source: Britannica

Kennedy took to national television and announced that the military found Soviet missiles in the Caribbean and said that he authorized a naval quarantine of the island. The word quarantine used specifically so as not to used the word blockade, which was, legally-speaking, an act of war. In practice, it was the same thing.

The world held its breath as Soviet ships steamed toward the US Navy line. News outlets put out wall-to-wall coverage of events. Everyone waited to see whether the Soviet ships would try to force their way through, or turn around.

Most did. But in one case, the Soviet diesel-electric submarine B-59 was too deep to be aware of the evolving situation. US destroyers started tailing the submarine in international waters, pinging loudly on sonar and dropping light depth-charges. A demand to surface. The captain, Valentin Savitsky, thought the Soviets and the US may be at war. He debated whether to use a nuclear-tipped torpedo on the tailing ships with the onboard political officer and the commander of the submarine detachment, Vasily Arkhipov. Policy was that a nuclear weapon launch required unanimous approval. The batteries onboard began to die. The air conditioners keeping the atmosphere cool in the B-59 began to fail and the temperature inside soared. They finally decided to surface. Arkhipov was credited with being the only one of the three deciders that opposed using the nuclear weapon.

B-59 with a US helicopter hovering above. Source.

Although no Soviet ships could bring new missiles into Cuba, the existing missiles on the island were operational. The Joint Chiefs of Staff drew up plans for a ground invasion and enormous conventional airstrikes to take out both ballistic and surface to air missile sites.

But Krushchev extended a deal to Kennedy to ease tensions from their fever-pitch. If the United States would withdraw its Jupiter medium-range ballistic missiles from Turkey, he would withdraw the Soviet missiles from Cuba.

With the bombing runs slated to begin the following Monday, Kennedy leapt at the offer. Both sides demobilized their respective missiles. Extinction averted again, for the moment.

Bad signals, faulty chips, and misbehaving radar

The North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) is responsible for monitoring the planet for any missile or aircraft headed in the direction of the United States or Canada. Although officially based at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado Springs, NORAD’s alternate command center resides in the Cheyenne Mountain Complex, one of the most hardened facilities in the world.

Entrance to the Cheyenne Mountain Complex. Source.

November 9, 1979. The computer screens at the Cheyenne Mountain Complex lit up with Soviet missiles. It looked like an enormous attack. Strikes were imminent, minutes away. Klaxons sounded at bomber bases around the country. Crews rushed to their planes. Fighters took to the sky. SAC, the Raven Rock Complex, and the Pentagon were notified. The entire military infrastructure prepared for the worst. As time went on, however, no bombs detonated. Radar and satellites couldn’t corroborate the launches. Shortly after the alarm, personnel at NORAD discovered that one of their technicians mistakenly placed a training tape into one of the computers. The “attack” was just a simulation.

June 3, 1980. Tensions with the Soviet Union were high after red troops poured into Afghanistan to defend the Communist regime, which seized power in Kabul in 1978, from the Mujahideen, a coalition of mainly Islamist, anti-government factions who rose up to fight the regime’s national reform efforts. In response, the United States led a boycott of the Moscow Olympics and imposed sanctions against the Soviets. They also began secretly providing arms to the Mujahideen.

It was in this environment that NORAD detected a launch of some 2200 missiles at the United States. Now, nearly every Russian silo was empty. Zbigniew Brzezinski, national security adviser to the President, who received the 2:30am emergency call, was about to phone the White House to have the President decide whether to retaliate, when General William E. Odom, Brzezinski’s assistant, called back a moment before. A faulty chip in one of the NORAD communications devices was reading out erroneous messages. No missiles inbound. Eric Schlosser writes in his book Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety: “The defective chip was replaced, at a cost of forty-six cents.”

September 26, 1983. Three weeks after Soviet fighters shot down Korean Airlines 007, a Boeing 747 carrying 269 civilian passengers (whom all died), after it strayed into Soviet airspace, the USSR was on high alert for a US response. The downing of flight 007 caused worldwide outrage, particularly from US President Ronald Reagan who called it a “crime against humanity.”

Stanislav Petrov, a lieutenant colonel in the Soviet Air Forces, was on duty in a Soviet command and control bunker south of Moscow when early-warning radar detected five inbound Minuteman ICBMs from the US. He puzzled over why an American attack would be so small, and decided not to relay the warning up his chain of command, assuming it was a false signal, which it was. Later investigations revealed that light reflected off of cloud vapor would periodically cause Soviet monitoring satellites to interpret missile launches. With his act of omission, Petrov is credited with likely averting a massive Soviet nuclear response and an ensuing exchange with the United States.

We still have problems, but it’s better than before

With the Cold War behind us and the titanic ideological altercations between Western Capitalism and Soviet Communism the stuff of history textbooks, global nuclear annihilation is no longer top-of-mind for most. Pandemics, the rise of artificial intelligence, and other fears creep in to take the lime-light of existential risk.

Schlosser points out that we’re not out of the woods. That citizens and policymakers shouldn’t lose sight of what’s at stake. Much of the information about the events above is sourced from his book, but it also recounts more modern mishaps that erode the confidence we may feel that the military has everything under control these days. With so many Minuteman and NORAD computer systems under the constant effects of weather, entropy and chance cirumstance, malfunctions still happen. Like in October of 2010, when the Air Force temporarily lost contact with 50 Minuteman IIIs near F. E. Warren Air Force base due to the incorrect replacement of a circuit board during maintenance. There is also the ever-present human factor to keep concerns alive.

In a more recent article, Schlosser shows that illegal drug use by US Air Force missile personnel is sometimes a problem, possibly because of the long, boring hours. In 2015 alone, three launch officers stationed at Malmstrom Air Force Base were thrown out of the service for drug use “including ecstasy, cocaine, and amphetamines” and a separate launch officer at Minot Air Force Base “was sentenced to twenty-five years in prison for heading a violent street gang, distributing drugs, sexually assaulting a girl under the age of sixteen, and using psilocybin, a powerful hallucinogen.” What might a future drug-abusing, gang-leading launch officer do some day?

Relations between the United States and Russia no longer signal an imminent nuclear exchange, but there are other bilateral beefs to keep an eye on too, such as the standoff between Pakistan and India, each nuclear powers.

However, lately, when sabres rattle and a US president or a foreign actor spout rhetoric to flex their nuclear muscles, we can take some solace in the fact that our nuclear demise has been much nearer in times past. At the time of this writing, superpower war and guaranteed, mutual destruction of the type that confronted President Kennedy, Nikita Krushchev, Ronald Reagan, or Mikhail Gorbachev doesn’t look to be in the cards. Because of this, deployed nuclear weapons in the United States and Russia shrink with each new arms reduction treaty. With these decreases also comes a lower probability of accidental detonations and more Broken Arrows. We’ve stepped back from the brink.

References:

- The End is Always Near, Dan Carlin

- Buzz One Four, Matt Mcormick

- The Bomb: Presidents, Generals and the Secret History of Nuclear War, Fred Kaplan

- Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety, Eric Schlosser

Further reading, listening and watching:

- The Bomb: Sam Harris interview with Fred Kaplan

- Dr. Strangelove Whisperings: Dan Carlin interview with Fred Kaplan

- Command and Control, PBS