The machinations of the Federal Reserve in the Coronavirus economy

The beating heart of the financial system is liquidity: Simply, the amount of money available to banks to lend and borrowers to spend. When times are good, there’s enough liquidity that banks lend can lend at attractive interest rates. Borrowers perceive less cost and risk to pay back these loans so they borrow more to fund new businesses, to employ more people, or to buy assets, growing the economy.

The flipside of growth is inflation. When buyers across the economy have more cash to spend, businesses charge more for the same amount of goods to maximize their earnings. A little inflation is generally a sign of a healthy economy, generally 1–2% year-over-year, but high inflation means that there’s something awry. Either consumers have lots of cash to spend, driving up prices, or something increases the cost of goods, like a natural disaster or a big supply cut, which makes them more expensive.

The Federal Reserve‘s job is to manage these inflation patterns and stabilize the U.S. financial system to keep the economy humming. One of the Fed’s main levers on inflation is the “Fed Funds Rate,” which is the interest rate commercial banks charge each other for loans to meet reserve requirements.

The Fed’s reserve requirements force US banks to keep a percentage of their deposits in cash, rather than lend them out. This is to ensure that they’re solvent in a financial panic. If a bank doesn’t have enough cash because it’s loaned out too much and too many people demand their deposits back at the same time, the bank can collapse. If banks go bust on a large scale, as they did during the Great Depression, the economic harm can be enormous and long-lasting. It’s like a financial cancer that metastasizes though the system, drying up cash. So, when banks are short of their reserve requirement, which they have to meet at the close of each business day, they borrow from one another at the Fed Funds Rate, or, in a last resort, borrow from the Fed itself at the Discount Window rate, which is slightly higher.

Many other interest rates like those for mortgages, checking accounts, credit cards, auto loans, and others benchmark off of the Fed Funds Rate, making it a uniquely powerful number.

But just because the Fed declares a new Fed Funds Rate doesn’t necessarily mean that banks start charging each other that amount of interest and that mortgages and credit cards suddenly adjust their short-term rates. The Fed has to take action to drive rates where it wants using Open Market Operations, meaning that it either buys or sells government securities to banks.

If the Fed wants to increase liquidity and heat up the economy, it lowers the target Fed Funds rate and buys US government securities (US Treasury bonds, notes, bills) from US commercial banks and deposits funds into their reserve accounts (which are held at Federal Reserve banks across America). With this influx of new cash, banks compete to lend money to one another to meet reserve requirements and rates go down.

If the Fed wants to decrease liquidity and pump the brakes on inflation, it increases the Fed Funds rate and sells US bonds to banks. This process extracts cash from the economy in exchange for a debt obligation from the US Treasury.

The Fed pulled out all the stops to fight the Corona-slump

In response to the economic chaos brought on by COVID-19, the Fed made several dramatic moves to flood the market with dirt-cheap credit and increase liquidity for lenders. It dropped the Fed Funds Rate target to between 0% and 0.25%, slashed the discount window rate to 0.25%, greatly expanded open market purchase and repurchase operations, and eliminated reserve requirements for US banks, among other things.

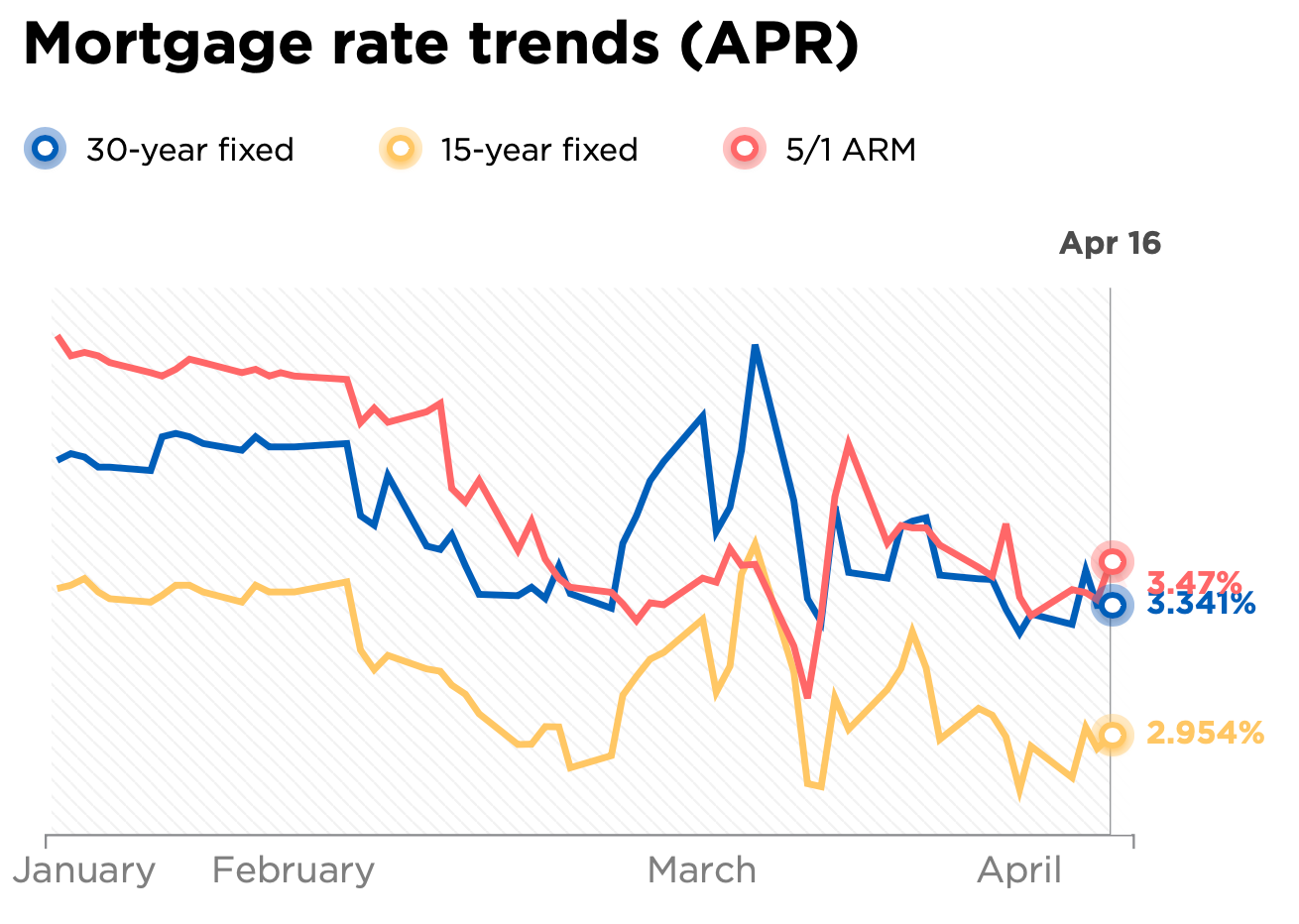

A 0%-ish Fed Funds target means that banks will be able to borrow Fed Funds from one another at essentially no cost, with rates falling somewhere underneath the 0.25% discount window. We should also expect to see interest rates for mortgages, savings accounts, credit cards, and other loans fall as well.

Mortgage rates show a downward trend after The Fed’s March announcements. Source: Nerdwallet.

The Fed said it would purchase $75 billion in US Treasury securities and $50 billion in mortgage-backed securities from banks daily to pump cash into the system. It’s also using a similar tool called repurchase operations to infuse even more.

Security repurchase agreements happen because banks and hedge funds don’t like to hold cash, since it doesn’t generate a return on its own. So, to raise liquid funds for a short time period to finance investments or loans, they’ll offer to sell securities (like US treasury bonds) to other banks (or the Fed)and agree to buy them back later at a higher price. According to the Brookings Institution: “Before coronavirus turmoil hit the market, the Fed was offering $100 billion in overnight repo and $20 billion in two-week repo. It has greatly expanded the program — both in the amounts offered and the length of the loans. It is offering $1 trillion in daily overnight repo, and $500 billion in one month and $500 billion in three-month repo.”

The Fed removed reserve requirements completely, reasoning that most banks hold reserves far in excess of what they need to. One of the causes of this is that the Fed started offering interest on excess reserves after the financial crisis began in 2008. But it also relaxed other capital buffer requirements like the Total Loss Absorbing Capacity (TLAC) regulation.

Despite these big policy changes and the $2 trillion CARES act payout to households and corporations in the US, we’ll likely have to make our way through some rough seas. It’s difficult to grow an economy under quarantine, even with basically unlimited access to credit.

Sources:

- https://www.brookings.edu/research/fed-response-to-covid19/

- https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/01/28/what-is-the-repo-market-and-why-does-it-matter/

- https://www.frbsf.org/education/publications/doctor-econ/2006/august/libor-federal-funds-rate-short-term/

- https://www.thebalance.com/fed-funds-rate-definition-impact-and-how-it-works-3306122

- https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20200315b.htm

- https://www.stlouisfed.org/in-plain-english/a-closer-look-at-open-market-operations